Then the final color of the pixel can be calculated as

Porter proposed the "Alpha channel"(1.[Porter 1984]) in 1984 which is widely established in real-time rendering to simulate the transparent effect.

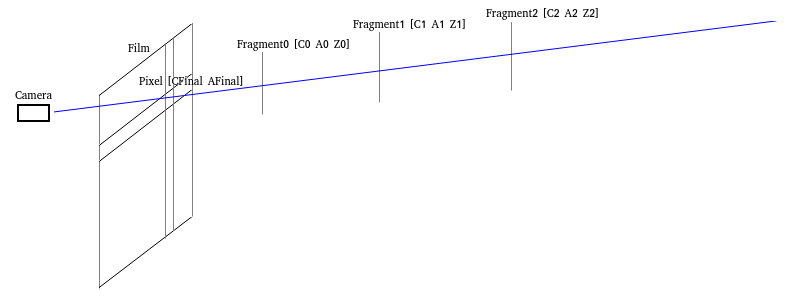

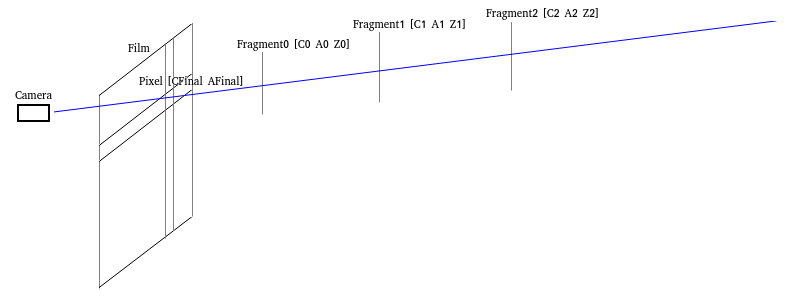

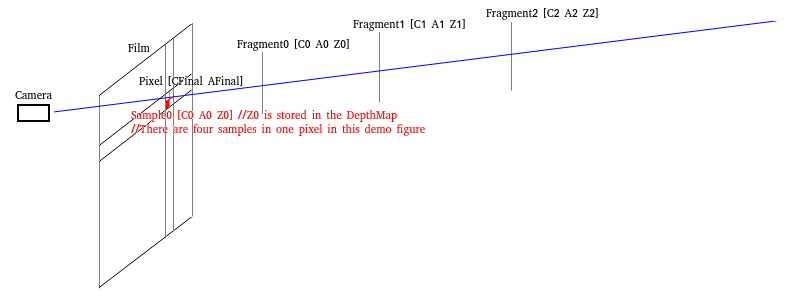

We assume that one "pixel" corresponds to a series of "fragments" which can be

treated as the triples

Then the final color of the pixel can be calculated as

The

Then the above equation can also be written as

Note that the physical meaning of the Alpha is the "partial coverage" rather than the "transmittance".

The Alpha stands for the ratio of the area covered by the fragments to the area covered by the pixel.

That's why we use the scalar "float" instead of the vector "RGB" to represent the Alpha.

This circumstance is also called the "Wavelength Independent" in some literatures.

For example, when we observe a red brick through a blue silk scarf, the color of the brick appears to be the

"addition" of the blue and red. The fibers of silk scarf are intrinsically opaque but there exist gaps

between the fibers. We see the brick through the gaps. Namely, the silk scarf "partially covers" the

brick.

However, the transmittance is "Wavelengh Dependent". If we observe a red brick through a blue plastic film, the color of the brick appears to be black (the "Multiplication" of the blue and red). The red brick only reflects the red light while the blue plastic film only allows blue light to pass through. All the reflected light of the red brick is absorbed by the blue plastic film and then the red brick appears to be black.

You can do the above two experiments by yourself.

If we demand the transmittance effect, the techniques related to the "Participating Media"(2.[Yusor 2013]、3.[Hoobler 2016]) should be used.

By the physical meaning of the Alpha, we can comprehend the visibility function

Some literatures treat the visibility function

In real time rendering, the classic method is to sort the transparent geometries and use the

"Over/Under Operation"(1.[Porter 1984]、4. [Dunn 2014]) to calculate the final color

1.OpaquePass

draw the opaque geometries and have the BackgroundColor and the BackgroundDepth.

2.TransparencyPass

use the BackgroundDepth for depth test (without depth write), sort the geometries from far to near/from near to far and use Over/Under Operation to calculate recursively.Over Operation

sort the fragments from far to near to use the Over Operation

Under Operation

sort the fragments from near to far to use the Under Operation

Note that thein Under Operation is exactly the visibility function above.

At last, the result image of the OpaquePass is treated as the fragments with "A=1 C=BackgroundColor" and added to the final color by the Under Operation.

By the mathematical induction, we can prove that the Over Operation and the Under Operation are

equivalent. Both can calculate the final color

Technically, the correctness of the Over/Under Operation can only be guaranteed by sorting the "fragments" from far to near/from near to far. However, in real time rendering, the sorting is based on the geometries not the fragments. If there exists interlacing inside the geometry, the order of the fragments will not follow and thus we have to explore the OIT(Order Independent Transparency) algorithm to settle this problem.

Note that keeping the geometries orderly also prohibits the batching of the geometries with the same material and thus results in extra state changing which is hostile to the performance.

Depth Peeling(5.[Everitt 2001]) is an archaic method which might be used in real time rendering.

1.OpaquePass

draw opaque geometries and have the BackgroundColor and the BackgroundDepth.

2.NearestLayerPass //GeometryPass

copy the BackgroundDepth to initialize the depth buffer

with depth test(NearerOrEqual) and depth write, sort the transparent geometries by [material, front-to-back] and draw them, having the NearestLayerColor and the NearestLayerDepth

add the NearestLayerColor to the final colorby Under Operation

//Note that the depth peeling doesn't depend on the order of the fragments and we sort the geometries from near to far is merely to improve the performance by the EarlyDepthTest.

3.SecondNearestLayerPass //GeometryPass copy the BackgroundDepth to initialize the depth buffer

with depth test(NearerOrEqual) and depth write, sort the transparent geometries by [material, front-to-back], bind the NearestLayerDepth to the SampledTextureUnit and draw them with discarding the fragments NearerOrEqual than the NearestLayerDepth explicitly in the fragment shader, having the SecondNearestLayerColor and the SecondNearestLayerDepth

add the SecondNearestLayerColor to the final colorby Under Operation

//Note that the depth peeling doesn't depend on the order of the fragments and we sort the geometries from near to far is merely to improve the performance by the EarlyDepthTest.

4.ThirdNearestLayerPass //GeometryPass copy the BackgroundDepth to initialize the depth buffer

with depth test(NearerOrEqual) and depth write, sort the transparent geometries by [material, front-to-back], bind the SecondNearestLayerDepth to the SampledTextureUnit and ...

//Note that the depth peeling doesn't depend on the order of the fragments and we sort the geometries from near to far is merely to improve the performance by the EarlyDepthTest.

The subsequent operations are similar to the above, omitted... //we can peel N layers by N geometry passes. The application can choose the proper N according to the requirements.

N+2.CompositePass //FullScreenTrianglePass

At last, the BackgroundColor by OpaquePass is added to the final color by the Under Operation.

Technically, it's legal to peel the layers from far to near and add them to the final color by the

Over Operation.

However, if the number of the geometry passes N is too low to peel all layers, the farthest/nearest layers will

be ignored when we use the Under/Over Operation.

Evidently, the visibility function

Evidently, the depth peeling has a fatal disadvantage that the number of the geometry passes is too high and the performance is too low and thus the depth peeling has never been popular since proposed decades ago.

The estimation of the visibility function

By this fact, Enderton proposed the "stochastic transparency"(6.[Enderton 2010]) in 2010 which is

based on the the principles of statistics and uses MSAA hardware to random sampling to estimate the visibility

function

With the MSAA on, we assume the relationship among the "pixel", "fragment" and

"sample" as the following figure:

one pixel corresponds to several samples (for example, in the above figure, one pixel corresponds to 4 samples,

namely, 4X MSAA) and at the same time one pixel corresponds to a series of fragments.

However, the same sample corresponding to the same pixel can only be occupied by one fragment of these fragments

corresponding to the same pixel(The storage is limited, which can hold only one fragment. That's evident).

At the same time, we assume that:

In addition, we assume that:

By setting the value of gl_SampleMask/SV_Coverage, we ensure that the probability of each sample be occupied by

the fragment [

With depth test and depth write, we ensure that the nearer fragment must overwrite the farther fragment and the

sample is occupied by the nearest fragment.

The probabilities of different fragments are uncorrelated.

We claim that for each sample [

Proof:

Since "the nearer fragment must overwrite the farther fragment", if "

Namely, the sample is not be occupied by the nearer fragments corresponding to the same pixel.

Evidently, the probability of "the sample is not be occupied by one fragment

Since "the probabilities of different fragments are uncorrelated", by the multiplication principle,

the probability of "the sample is not be occupied by the nearer fragments corresponding to the same

pixel" is

Besides, we assume that:

One pixel corresponds to S samples, namely, S-X MSAA.

We claim that if the count of the samples such that "

Proof: Evidently, this is immediate from the above proposition.

Since we can get the value of

Note that the extension "ARB_texture_multisample" should be enabled to use texelFetch on sampler2DMS

in OpenGL.

We should use the knowledge of statistics to prove why we can estimate and thus the proof is omitted.

We claim that

Proof:

Prove by the mathematical induction.

1.basis:

when n=0:

left =

=

=

=

right =

=

=

left = right the equation holds

2.inductive step:

we assume that the proposition holds for n=k.

when n=k+1:

left =

=

=

=

=

=

right =

left = right the equation holds

Evidently, the expected value of

Since

The Alpha correction can be considered as the normalizing of the

This means that we assume that

We should use the knowledge of statistics to explain the meaning of the Alpha correction and thus the explanation is omitted.

1.OpaquePass

draw the opaque geometries and have the BackgroundColor and the BackgroundDepth.

2.StochasticDepthPass //GeometryPass

copy the BackgroundDepth to initialize the depth buffer

with MSAA, with depth test(NearerOrEqual) and depth write, sort the transparent geometries by [material, front-to-back] and draw them with setting the pseudo random value of gl_SampleMask/SV_Coverage by theof [ ], having the StochasticDepth

Note that:

2-1.The stochastic transparency doesn't depend on the order of the fragments and we sort the geometries from near to far is merely to improve the performance by the EarlyDepthTest.

2-2.Turning on MSAA in StochasticDepthPass is to random sample and the stochastic transparency intrinsically doesn't demand other passes to turn on the MSAA.

If the application demands the effect of "Spatial AntiAliasing", the application can turn on MASS in other passes(Evidently, the application use arbitrary algorithms(for example, the FAXX) in other passes).

These's no relationship between the MSAA used for random sampling (in StochasticDepthPass) and the MSAA used for spatial antialiasing (in other passes). For example, we can use 8X MASS in StochasticDepthPass while use 4X MSAA in other passes.

2-3.To ensure the uncorrelation among fragments, we must use pseudo random value rather than the "AlphaToCoverage" hardware feature.

2-4.The depth value used in AccumulatePass is the value of the shading position not the value of the sampling position. To be consistant, we prefer to write the depth (value of the shading position) to gl_FragDepth/SV_Depth in the fragment shader.

2-5.By the limit of the hardware, the maximum sample count of MSAA is 8X MSAA. The author (6.[Enderton 2010]) proposed that we can use multiple passes to simulate more sample counts. Due to the performance issue, we only use one pass.

3.AccumulateAndTotalAlphaPass //GeometryPass

copy the BackgroundDepth to initialize the depth buffer

with depth test without depth write, with MRT and SeparateBlend/IndependentBlend, sort the transparent geometries by [material], bind the StochasticDepth to the SampledTextureUnit and draw them with estimateby sampling the texture in fragment shader, having the StochasticColor, CorrectAlphaTotal and StochasticTotalAlpha

Note that:

3-1.Since the depth write is turned off, the order of the geometries doesn't impact on the performance and thus we sort the geometries only by the material.

3-2.We have that "StochasticColor =", "CorrectAlphaTotal = " and "StochasticTotalAlpha = ".

3-3.The relationship between the AlphaTotal and the TotalAlpha is TotalAlpha = 1 – AlphaTotal. The term "TotalAlpha" is from the stochastic transparency(6.[Enderton 2010]) while the term "AlphaTotal" is from the Under Operation(1.[Porter 1984]、4. [Dunn 2014]).

3-4.The StochasticTotalAlpha is only used when the Alpha correction is turned on. This means that we can reduce one RT if we don't turn on the Alpha correction.

3-5.The author(6.[Enderton 2010]) use two separate passes AccumulatePass(which calculates the StochasticColor and the StochasticTotalAlpha) and TotalAlphaPass(which calculates CorrectAlphaTotal). However, we can totally merge them into a single pass. Maybe the SeparateBlend/IndependentBlend was not supported by the hardware when the author published the paper.

4.CompositePass //FullScreenTrianglePass

Without the Alpha correction, the total contribution of the transparent geometries:

TransparentColor == StochasticColor

With the Alpha correction, the total contribution of the transparent geometries:

TransparentColor =

=

=

Note that the StochasticTotalAlpha of opaque geometries is evidently zero. However, due to the random sampling, the StochasticTotalAlpha of the transparent geometries can be zero as well.

Then, add the TransparentColor to the final color

by the Over Operation:

= TransparentColor + CorrectAlphaTotal × BackgroundColor

Note that the BackgroundColor has been added to the color buffer. We can output the TransparentColor and CorrectAlphaTotal in the fragment shader and use the Alpha blend hardware feature to implement the Over Operation.

The stochastic transparency is intrinsically suitable to mobile GPU.

In the traditional desktop GPU, the performance bottleneck is the MSAA. Since one pixel corresponds to S samples, the bandwidth is increased by S times.

However, in the mobile GPU, this problem has been solved effectively. We can keep the MSAA image in the Tile/On-Chip Memory and discard the MSAA image when the renderpass ends without writing to the main memory. This means that the bandwidth can be decreased to almost zero.

The Vulkan/Metal API allows the application to set this configuration explicitly:

Use the "VK_IMAGE_USAGE_TRANSIENT_ATTACHMENT_BIT"/"MTLStorageModeMemoryless" to set the

storage mode of the image to the Tile/On-Chip Memory explicitly.

And the images with this storage mode prohibit to be read by the traditional sampled texture unit in the

fragment shader and must be read by the "Subpass Input"/"[color(m)]Attribute".

The OpenGL API doesn't allow the application to set this configuration explicitly but we can use "FrameBufferFetch"/"PixelLocalStorage"(16.[Bjorge 2014]) to indicate our purpose.

In Vulkan, one "RenderPass" consists of several "SubPass". The MSAA simple count of different attachments of the same RenderPass may not be the same. However, the MSAA sample count of the attachments refered by the same SubPass must be the same and the MSAA sample count is also expected to be the same as the count in MultisampleState of the PipelineState when issuing DrawCall.

The stochastic transparency can be implemented in one renderPass as the following: //We suppose the application doesn't turn on the MSAA for "Spatial AntiAliasing".

RenderPass

Attachments

0.FinalColor

1.BackgroundDepth

2.StochasticDepth (MSAA)

3.StochasticColor

4.CorrectAlphaTotal

5.StochasticTotalAlpha

SubPasses

0.OpaquePass

ColorAttachments

0.FinalColor //BackgroundColor->FinalColor

DepthStencilAttachment

1.BackgroundDepth

1.CopyPass //Mentioned in StochasticDepthPass //Rasterization MSAA

InputAttachments

1.BackGroupDepth

ColorAttachments

2.StochasticDepth (MSAA)

2.StochasticDepthPass //Rasterization MSAA

DepthStencilAttachments

2.StochasticDepth (MSAA)

3.AccumulateAndTotalAlphaPass

InputAttachments

2.StochasticDepth (MSAA)

ColorAttachments

3.StochasticColor

4.CorrectAlphaTotal

5.StochasticTotalAlpha

DepthStencilAttachments

1.BackGroupDepth

4.CompositePass

InputAttachments

3.StochasticColor

4.CorrectAlphaTotal

5.StochasticTotalAlpha

ColorAttachments

0.FinalColor //TransparentColor

(+=(CorrectAlphaTotal×BackgroundColor))->FinalColor //implement the Over Operation by the Alpha blend hardware feature

Dependency:

0.SrcSubPass:0->DstSubPass:1

//DepthStencilAttachment->InputAttachment: 1.BackGroupDepth

1.SrcSubPass:1->DstSubPass:2

//ColorAttachment->DepthStencilAttachment: 2.StochasticDepth (MSAA)

2.SrcSubPass:2->DstSubPass:3

//DepthStencilAttachment->InputAttachment: 2.StochasticDepth (MSAA)

3.SrcSubPass:3->DstSubPass:4

//ColorAttachment->ColorAttachment: 0.FinalColor

//ColorAttachment->InputAttachment: 3.StochasticColor

//ColorAttachment->InputAttachment: 4.CorrectAlphaTotal

//ColorAttachment->InputAttachment: 5.StochasticTotalAlpha

//SubPassDependencyChain: 0->1->2->3->4

In Metal, there is no such thing like InputAttachment. We instead use the [color(m)]Attribute in

fragment shader to read the ColorAttachment.

However, this design introduces the limit that the [color(m)]Attribute only permits us to read the

ColorAttachment in the fragment shader and we have no method to read the DepthAttachment. We have to use an

extra ColorAttachment to store the Depth(17.[Apple]) although this may allow us to save the bandwidth by writing

the lower precise depth to the ColorAttachment and discarding the DepthAttachment.

This limit may be related to the explanation of the

"D3D12_RESOURCE_FLAG_DENY_SHADER_RESOURCE"(18.[Microsoft]). This means that for Apple's GPU, the

performance may be improved by prohibiting reading the DepthAttachment.

Besides, there is no equivalent of "subpassInputMS" in Metal. While turning on the MSAA in

Metal, the fragment shader is excuted isolatedly for each sample, we can only use the [color(m)]Attribute to

read the value of one sample not all samples in the pixel and thus we can't calculate the

However, we may simulate the "subpassInputMS" by multiple ColorAttachments without MSAA. Since we turn off the MSAA, there exists only one sample in the DepthAttachment and thus we can't perform MSAA depth test by the hardware feature. This means that we have to simulate the depth test by programmable blending which will be explained later in the K-Buffer.

Evidently, the simulation is expected to be hostile to the performance and I don't suggest using this method in Metal.

Since MSAA is efficient on mobile GPU, the stochastic transparency is intrinsically suitable to mobile GPU. We can use the modern Vulkan API to fully explore the advantages of the mobile GPU.

However, due to the limit by the design of the Metal, I don't suggest using the stochastic transparency in Metal.

Evidently, the vertex shader doesn't read or write the ColorAttachment and thus doesn't benifit from

the Tile/On-Chip Memory of the mobile GPU. The mobile GPU prefers the fragment processing to the vertex

processing(10.[Harris 2019]).

The stochastic transparency still need to be improved since we still have two geometry

passes(StochasticDepthPass and AccumulateAndTotalAlphaPass) which may cause the vertex processing to be the

performance bottleneck.

The stochastic transparency introduces error by itself due to the random sampling while the Alpha correction eliminates the noise effectively and thus the noise impacts little.

The github address https://github.com/YuqiaoZhang/StochasticTransparency

The demo was originally the "StochasticTransparency" of the "NVIDIA SDK11

Samples"(9.[Bavoil 2011]). However, there are three fatal problems in the original code provide by the

NVIDIA:

1."Turning on MSAA in StochasticDepthPass is to random sample and the stochastic transparency intrinsically

doesn't demand other passes to turn on the MSAA." The original code provided by the NVIDIA turns on the

MSAA in all passes and thus the frame rate of the stochastic transparency is unexpectedly lower than the depth

peeling. I turn off all the unnecessary MSAA and the frame rate increases from 670 to 1170 while the frame rate

of deep peeling is 1070.

2."The author use two separate passes AccumulatePass and TotalAlphaPass. However, we can totally merge them

into a single pass." The original code provided by the NVIDIA follows the author and use two separate

passes. I merge the separate passes and the frame rate increases from 1170 to 1370.

3."The depth value used in AccumulatePass is the value of the shading position not the value of the

sampling position. To be consistant, we prefer to write the depth (value of the shading position) to

gl_FragDepth/SV_Depth in the fragment shader." The original code provided by the NVIDIA doesn't do this.

However, the Alpha correction fixes the error well and there's little impaction on the effect.

Carpenter proposed the "A-Buffer" (11.[Carpenter 1984]) in the same year when Porter

proposed the Alpha channel. In the A-Buffer, each pixel corresponds to a list in which all fragments

corresponding to this pixel are stored. After sorting the fragments in the list by the depth, evidently we can

use Over/Under operation to calculate the final color

Although A-Buffer can be implemented by UAV/StorageImage and atomic operations at present, the implementation is

very tedious and inelegant. Besides, the performance of the list is low since the address of the list is not

continuous and thus unfriendly to the cache. Thus there is almost no implementation in reality.

Bavoil improved the A-Buffer and proposed K-Buffer (12.[Bavoil 2007]) in 2007. In K-Buffer, we limit the number of the fragments corresponding to each pixel to no more than K. With this limit, the K-Buffer can be implemented more elegantly and efficiently.

In the renderpass in which we generate the K-Buffer, the following RMW operation is performed on each

fragment:

1. Read: read the (at most K) fragments corresponding to the same pixel from K-Buffer

2. Modify: use the information of the current fragment and modified the (at most K) fragments which have been

read from the K-Buffer

3. Write: write the (at most K) fragments which have been modified to the K-Buffer

For the current hardware, we can immediately implement the RMW operation by the UAV/StorageImage. However, things are far from simple. In general, the RMW operations performed on the fragments corresponding to the same pixel should be mutually exclusive to ensure the correctness.

Although the API guarantees the order and dependency of different draw calls, the GPU designers always tend to full explore the parallelism to improve the performance. In general, the GPU may still execute these draw calls in parallel and merely synchronize at some points.

The API doesn't guarantee the order or dependency of the executions of the fragments (corresponding to the same pixel) inside the same draw call. Evidently, the executions can be considered to be parallel since the GPU is intrinsically parallel.

The desktop GPU is "Sort-Last Fragment" (13.[Ragan-Kelley 2011]). The parallelism of the fragments is expected to be high since the synchronization occurs at the "Reorder Buffer" (13.[Ragan-Kelley 2011]) which is after the fragment shader and just before the Alpha blend.

The mobile GPU is "Tile-Based Sort-Middle" (13.[Ragan-Kelley 2011]). The executions of the fragments corresponding to the same pixel inside the same draw call can be considered to be serial (13.[Ragan-Kelley 2011]) since there doesn't exist the "Reorder Buffer". However, we shouldn't rely on this since the API doesn't guarantee that.

Bavoil proposed two hardware proposals the "Fragment Scheduling" and the "Programmable Blending" to solve this problem in 2007 (12.[Bavoil 2007]). Both two proposals have been widely supported by the hardware in reality at present.

The fragment scheduling corresponds to the RasterOrderView/FragmentShaderInterlock/RasterOrderGroup(14.[D 2015], 15.[D 2017]) at present which is generally suitable to the desktop GPU.

The pseudo code to implement the K-Buffer by the fragment scheduling is generally as the following:

// This part of code doesn't need to be mutually exclusive

calcalte lighting and shading ...

// Enter the critical section

#if RasterOrderView // Direct3D

read from ROV

#elif FragmentShaderInterlock // OpenGL/Vulkan

beginInvocationInterlockARB

#elif RasterOrderGroup // Metal

read from ROG

#endif

// This part of code is within the protection of the critical section

perform the RMW operation on the K-Buffer ...

// Leave the critical section

#if RasterOrderView // Direct3D

write to ROV

#elif FragmentShaderInterlock // OpenGL/Vulkan

endInvocationInterlockARB

#elif RasterOrderGroup // Metal

write to ROG

#endif

In theory, the contents which we read from or write to the ROV/ROG is not important since we merely read or write to enter/leave the critical section. Thus the proposal of "FragmentShaderInterlock" is more elegant. We don't have to read from or write to the ROV/ROG when we perform the RMW operation on the K-Buffer and the regular UAV/StorageImage(14.[D 2017]) can be used since the related code has been within the protection of the critical section.

The programmable blending, which is generally suitable for the mobile GPU, corresponds to the GL_EXT_shader_framebuffer_fetch extension in OpenGL, the [[color(m)]] attribute in Metal ("Table 5.5. Attributes for fragment function input arguments" of Metal Shading Language Specification) and the VK_EXT_rasterization_order_attachment_access extension in Vulkan.

The programmable blending allows the fragment shader to perform RMW as an atomic operation on the color attachment. The hardware guarantees the mutual exclusion of the fragments corresponding to the same pixel automatically.

We can enable the MRT and implement the K-Buffer by programmable blending. We assume that one pixel corresponds to four [C A Z] fragments in the K-Buffer and the related Metal code is generally as the following:

struct KBuffer_ColorAttachment

{

//In general, [[color(0)]] is used to store the CFinal

half4 C0A0[[color(1)]]; //R8G8B8A8_UNORM

half4 C1A1[[color(2)]]; //R8G8B8A8_UNORM

half4 C2A2[[color(3)]]; //R8G8B8A8_UNORM

half4 C3A3[[color(4)]]; //R8G8B8A8_UNORM

half4 Z0123[[color(5)]]; //R16G16B16A16_FLOAT

};

struct KBuffer_Local

{

half4 CA[4]

half Z[4]

};

fragment KBuffer_ColorAttachment KBufferPass_FragmentMain(..., KBuffer_ColorAttachment kbuffer_in)

{

// This part of code doesn't need to be mutually exclusive

CA = CalcalteLighting_And_Shading(...)

// In general, "Z" denotes position.z

Z = ...

KBuffer_Local kbuffer_local;

// Read K-Buffer

// We enter the critical section automatically when we read the ColorAttachment

kbuffer_local.Z[0] = kbuffer_in.Z0123.r;

kbuffer_local.Z[1] = kbuffer_in.Z0123.g;

kbuffer_local.Z[2] = kbuffer_in.Z0123.b;

kbuffer_local.Z[3] = kbuffer_in.Z0123.a;

kbuffer_local.CA[0] = kbuffer_in.C0A0;

kbuffer_local.CA[1] = kbuffer_in.C1A1;

kbuffer_local.CA[2] = kbuffer_in.C2A2;

kbuffer_local.CA[3] = kbuffer_in.C3A3;

// Modify K-Buffer

// This part of code is within the protection of the critical section

... (The concrete code depends on the requirements of the application)

// Write K-Buffer

// We leave the critical section automatically after we write the ColorAttachment

KBuffer_ColorAttachment kbuffer_out;

kbuffer_out.C0A0 = kbuffer_local.CA[0];

kbuffer_out.C1A1 = kbuffer_local.CA[1];

kbuffer_out.C2A2 = kbuffer_local.CA[2];

kbuffer_out.C3A3 = kbuffer_local.CA[3];

kbuffer_out.Z0123 = half4(kbuffer_local.Z[0], kbuffer_local.Z[1], kbuffer_local.Z[2], kbuffer_local.Z[3]);

return kbuffer_out;

}

Salvi proposed three algorithms which are all based on the K-Buffer in 2010, 2011 and 2014(19.[Salvi 2010], 20.[Salvi 2011], 21.[Salvi 2014]) and we intend to explain the lastest one which is called the MLAB proposed in 2014.

In MLAB, the format of the fragments in K-Buffer is [

The algorithm is generally as the following:

1. Initializes the fragments in the K-Buffer to the "empty fragment" which is "

2. When we generate the K-Buffer, the modify operation performed on the K-Buffer is to sort the fragments from

near to far based on the

Evidently we have K+1 fragments at present. Then the modify operation will merge the two farthest fragments into

one fragment based on the rule of Under operation such that [

Evidently, if we insert another fragment nearer than the fragment merged by two fragments, there exists error.

By Salvi, the error intruduced by the two farthest fragments is the lowest since the visibility function

3. Based on the generated K-Buffer, we calculate the total contribution of the transparent geometries to the

final color

1. OpaquePass

draw the opaque geometries and have the BackgroundColor and the BackgroundDepth.2. KBufferPass // GeometryPass

reuse the BackgroundDepth by the OpaquePass

use clear load_op to initilize the fragments in the K-Buffer to the "empty fragment" [ 0 0 farthest]

with depth test without depth write, sort the transparent geometries by [material] and draw them to generate the K-Buffer

Note that since the depth write is turned off, the order of the geometries doesn't impact on the performance and thus we sort the geometries only by the material.3. CompositePass // FullScreenTrianglePass

Based on the generated K-Buffer, use the Under operation to calculate the total contribution of the transparent geometries to the final color: TransparentColor and AlphaTotal Then, add the TransparentColor to the final color

by the Over Operation:

= TransparentColor + CorrectAlphaTotal × BackgroundColor)

Note that the BackgroundColor has been added to the color buffer. We can output the TransparentColor and CorrectAlphaTotal in the fragment shader and use the Alpha blend hardware feature to implement the Over Operation.

The K-Buffer is intrinsically suitable to mobile GPU.

In the traditional desktop GPU, the bandwidth is increased by K times due to the K-Buffer.

However, in the mobile GPU, we can keep the K-Buffer in the Tile/On-Chip Memory and discard the K-Buffer when the renderpass ends without writing to the main memory. This means that the bandwidth can be decreased to almost zero.

The K-Buffer can be implemented by the VK_EXT_rasterization_order_attachment_access extension in Vulkan.

However, this extension has not been widely supported on Android devices.

The K-Buffer can be implemented in one renderPass as the following: // We assume that the K of K-Buffer equals four.

RenderPassDescriptor:

ColorAttachment:

0.FinalColor // Load:Clear // Store:Store // Format:R10G10B10A2_UNORM // HDR10

1.xyz:A0*C0 w:1-A0 //Load:Clear // ClearValue:[ 0 0 0 1 ] //Store:DontCare //Format:R16G16B16A16_FLOAT

// The size of the PixelStorage is limited(A7-128bit A8\A9\A10-256bit A11-512bit)

// Since the visibility function is monotonically decreasing and the farther fragments generally contribute introduce the lowest error, we prefer to reduce the precision of the farther fragments.

2.xyz:A1*C1 w:1-A1 // Load:Clear // ClearValue:[ 0 0 0 1 ] // Store:DontCare // Format:R8G8B8A8_UNORM

3.xyz:A2*C2 w:1-A2 // Load:Clear // ClearValue:[ 0 0 0 1 ] // Store:DontCare // Format:R8G8B8A8_UNORM

4.xyz:A3*C3 w:1-A3 // Load:Clear // ClearValue:[ 0 0 0 1 ] // Store:DontCare // Format:R8G8B8A8_UNORM

5.Z0123 // Load:Clear // ClearValue:[ farthest farthest farthest farthest ] // Store:DontCare // Format:R16G16B16A16_FLOAT

DepthAttachment:

Depth // Load:Clear // Store:DontCare

RenderCommandEncoder:

0.OpaquePass:

BackgroundColor->Color[0]

BackgroundDepth->Depth

1.KBufferPass:

Read: Color[1]/Color[2]/Color[3]/Color[4]/Color[5] -> 4 Fragments

Modify: ...

Write: 4 Fragments -> Color[1]/Color[2]/Color[3]/Color[4]/Color[5]

// reuse the BackgroundDepth

3.CompositePass:

Color[1]/Color[2]/Color[3]/Color[4]/Color[5] -> ...

... -> TransparentColor

... -> AlphaTotal

Color[0] -> BackgroundColor

TransparentColor+AlphaTotal*BackgroundColor -> Color[0]

Since the K-Buffer is efficient on mobile GPU, the MLAB is intrinsically suitable to mobile GPU. We can use the modern Metal API to fully explore the advantages of the mobile GPU.

Compared to the stochastic transparency, there is only one geometry pass in MLAB. This is beneficial to the mobile GPU since the vertex processing is not efficient on the mobile GPU.

Besides, for the mobile GPU, the executions of the fragments corresponding to the same pixel inside

the same draw call is intrinsically serial (13.[Ragan-Kelley 2011]) and thus the mutual exclusion can be

considered to introduce little overhead.

However, for the desktop GPU, mutual exclusion of the RMW operation limits the parallelism of the fragments and

introduces extra overhead which is related to the "Depth Complexity" of the scene.

When we insert another fragment nearer than the fragment merged by two fragments, we introduce

error.

However, since the visibility function

The github address https://github.com/HanetakaChou/MultiLayerAlphaBlending

The demo was originally the "Order Independent Transparency with Imageblocks" of the "Metal Sample Code"(22.[Imbrogno 2017]). However, the original code provide by the Apple depends on the feature Imageblock which is only available on A11 and later GPU. The Imageblock is intrinsically to customize the format of the framebuffer which is not related to the mutual exclusion of the RMW operation at all. Thus I have modified the demo and use the \[[Color(m)]] Attributeto implement the related code and the demo can be run on A8 and later GPU.

The relationship of the features between Metal and OpenGL:

\[[Color(m)]] Attribute <-> FrameBufferFetch // To support the programmable blending

ImageBlock <-> PixelLocalStorage // To customize the format of the framebuffer

The estimation of the visibility function

Also by this fact, McGuire proposed the "Weighted Blending"(23.[McGuire 2013], 4.[Dunn 2014]) in 2013

which uses a predefined weighted function

By McGuire, the nearest fragments might contribute too much to the final color if the weighted

function only depended on the

Besides, McGuire proposed three suggested weighted function as the following:

1.

2.

3.

Verified by McGuire, the effect seems good when the

Note that the weighted function may exceed 1 when the fragment is very near while the visibility function is

evidently less or equal than 1.

We have proved that

The normalization means that we assume that

1.OpaquePass

draw the opaque geometries and have the BackgroundColor and the BackgroundDepth.

2.AccumulateAndTotalAlphaPass //GeometryPass initilize the depth with the BackgroundDepth

with depth test without depth write, sort the transparent geometries by [material] and draw them, having WeightedColor=, CorrectAlphaTotal= and WeightedTotalAlpha=

Note that:

1.Since the depth write is turned off, the order of the geometries doesn't impact on the performance and thus we sort the geometries only by the material.

2.The relationship between the AlphaTotal and the TotalAlpha is TotalAlpha = 1 – AlphaTotal as stated in the stochastic transparency.

3.CompositePass //FullScreenTrianglePass

The total contribution of the transparent geometries:

TransparentColor=

Then, add the TransparentColor to the final color

by the Over Operation:

= TransparentColor + CorrectAlphaTotal × BackgroundColor)

Note that the BackgroundColor has been added to the color buffer. We can output the TransparentColor and CorrectAlphaTotal in the fragment shader and use the Alpha blend hardware feature to implement the Over Operation.

The weighted blending uses the predefined weighted function

To some extent, the weighted blending is considered as a simplified version of the stochastic transparency which

omits the StochasticDepthPass.

Consequently, the error of the weighted blending is highest of all OIT algorthims since the weighted function

The github address https://github.com/YuqiaoZhang/WeightedBlendedOIT

The demo was originally the "Weighted Blended Order-independent Transparency" of the "NVIDIA GameWorks Vulkan and OpenGL Samples"(24.[NVIDIA]). The weighted blended is the simplest of the all OIT algorithms and I haven't made any substantial changes to the demo.

1.[Porter 1984] Thomas Porter, Tom

Duff. "Compositing Digital Images." SIGGRAPH 1984.

2.[Yusor 2013] Egor Yusor. "Practical Implementation of Light Scattering Effects Using Epipolar Sampling

and 1D Min/Max Binary Trees." GDC 2013. First-Edition

Second-Edition

Third-Edition

3.[Hoobler 2016] Nathan Hoobler. "Fast, Flexible,

Physically-Based Volumetric Light Scattering." GDC 2016.

4.[Dunn 2014] Alex Dunn.

"Transparency (or Translucency) Rendering." NVIDIA GameWorks Blog 2014.

5.[Everitt 2001] Cass Everitt.

"Interactive Order-Independent Transparency." NVIDIA WhitePaper 2001.

6.[Enderton 2010] Eric Enderton, Erik

Sintorn, Peter Shirley, David Luebke. "Stochastic Transparency." SIGGRAPH 2010.

7.[Laine 2011] Samuli Laine,

Tero Karras. "Stratified Sampling for Stochastic Transparency." EGSR 2011.

8.[McGuire 2011] Morgan McGuire,

Eric Enderton. "Colored Stochastic Shadow Maps". SIGGRAPH 2011.

9.[Bavoil 2011] Louis Bavoil, Eric Enderton.

"Constant-Memory Order-Independent Transparency Techniques." NVIDIA SDK11 Samples /

StochasticTransparency 2011.

10.[Harris 2019] Pete Harris.

"Arm Mali GPUs Best Practices Developer Guide." ARM Developer 2019.

11.[Carpenter 1984] Loren Carpenter. "The A-buffer, an

Antialiased Hidden Surface Method." SIGGRAPH 1984.

12.[Bavoil 2007] Louis Bavoil, Steven Callahan, Aaron

Lefohn, Joao Comba, Claudio Silva. "Multi-fragment Effects on the GPU using the k-Buffer."

SIGGRAPH 2007.

13.[Ragan-Kelley 2011] Jonathan Ragan-Kelley,

Jaakko Lehtinen, Jiawen Chen, Michael Doggett, Frédo Durand. "Decoupled Sampling for Graphics

Pipelines." ACM TOG 2011.

14.[D 2015] Leigh D.

"Rasterizer Order Views 101: a Primer." Intel Developer Zone 2015.

15.[D 2017] Leigh

D. "Order-Independent Transparency Approximation with Raster Order Views (Update 2017)." Intel

Developer Zone 2017.

16.[Bjorge 2014] Marius

Bjorge, Sam Martin, Sandeep Kakarlapudi, Jan-Harald Fredriksen. "Efficient Rendering with Tile Local

Storage." SIGGRAPH 2014.

17.[Apple] Metal Sample Code /

Deferred Lighting

18.[Microsoft] Direct3D 12

Graphics / D3D12.h / D3D12_RESOURCE_FLAGS enumeration

19.[Salvi 2010] Marco

Salvi,Kiril Vidimce, Andrew Lauritzen, Aaron Lefohn. "Adaptive Volumetric Shadow Maps." EGSR

2010.

20.[Salvi 2011] Marco Salvi,

Jefferson Montgomery, Aaron Lefohn. "Adaptive Transparency." HPG 2011.

21.[Salvi 2014] Marco Salvi,

Karthik Vaidyanathan. "Multi-layer Alpha Blending." SIGGRAPH 2014.

22.[Imbrogno 2017] Michael Imbrogno.

"Metal 2 on A11 – Imageblocks." Apple Developer 2017.

23.[McGuire 2013] Morgan McGuire, Louis Bavoil. "Weighted

Blended Order-Independent Transparency. " JCGT 2013.

24.[NVIDIA] NVIDIA

GameWorks Vulkan and OpenGL Samples / Weighted Blended Order-independent Transparency